Abstract

Purpose

Approximately 50% of cancer survivors experience moderate-severe fear of cancer recurrence (FCR). Self-guided digital interventions have potential to address the high level of FCR-related unmet needs at scale, but existing digital interventions have demonstrated variable engagement and efficacy. This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear, a five-module self-guided digital FCR intervention.

Methods

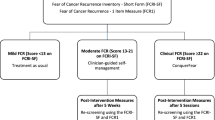

Eligible curatively treated breast cancer survivors were recruited. Participants reporting clinically significant FCR (≥ 13 on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory-Short Form; FCRI-SF) were given access to iConquerFear. Feasibility was indicated by > 50% of eligible participants enrolling in iConquerFear and recording moderate (≥ 120 min) or greater usage. Preliminary efficacy was evaluated via changes in self-reported FCR severity, anxiety, depression, intrusions and metacognitions from baseline to immediately and 3 months post-intervention.

Results

Fifty-four (83%) of 65 eligible participants enrolled in iConquerFear; six subsequently withdrew. Thirty-nine (83%) participants recorded moderate (n = 24; 120–599 min) or high (n = 15; ≥ 600 min) usage. Engagement levels increased with participant age (p = 0.043), but were lower in participants with higher baseline FCR (p = 0.028). Qualitative feedback indicated engagement was sometimes limited by difficulties with navigation and relating to featured survivors. Participants reported significantly improved FCR (mean reduction (95%CI): baseline to post-intervention − 3.44 (− 5.18, − 1.71), baseline to 3-month follow-up − 4.52 (− 6.25, − 2.78), p = < 0.001).

Conclusion

iConquerFear is a feasible and potentially efficacious intervention for reducing FCR in breast cancer survivors. Easier navigation and more relatable examples may enhance engagement.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

iConquerFear may help address moderate but burdensome FCR levels in cancer survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There are an estimated 43 million people living with and beyond cancer (hereafter referred to as cancer survivors). Cancer survivors’ most commonly reported unmet supportive care need is for help managing fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) [1], defined as fear, worry or concern about cancer returning or progressing [2]. Approximately half of cancer survivors experience clinically significant FCR [3, 4], which is associated with psychological distress, poorer quality of life (QoL) and greater healthcare use [1, 5]. FCR is more prevalent amongst survivors who are female [1, 4, 6] and younger [1, 4, 6] and experience physical symptoms [1, 7,8,9]. If untreated, FCR can persist for many years, highlighting the need for intervention [1, 10, 11].

Existing interventions (mostly face-to-face) have demonstrated efficacy in reducing FCR and associated psychological distress and QoL impairment [12, 13]. For example, ConquerFear, a 5-session therapist-delivered treatment including contemporary cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches (i.e. Metacognitive and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [14]), significantly improved FCR, cancer-related distress, anxiety and emotional QoL, with benefits maintained 6 months post-intervention [15]. However, barriers to face-to-face treatment, including distance, work, disease burden [16, 17] and more recently the COVID-19 pandemic limiting access to care, highlight the need for remotely delivered interventions [18]. Developing and evaluating more accessible FCR treatments have been identified as top international FCR research priorities [19]. Digital interventions can improve access to psychosocial support and facilitate self-management by survivors [17, 20, 21]. While survivors with severe FCR may need more intensive support [22], self-guided digital interventions may be appropriate for survivors with more moderate FCR levels [22, 23].

Digital interventions have demonstrated mixed results in reducing psychological burdens such as FCR [24]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 articles found comparable efficacy of face-to-face and online interventions for improving the psycho-emotional state of cancer survivors [25]. A meta-analysis of FCR interventions found a larger effect size for face-to-face (n = 18; g = 0.38) versus remotely delivered (n = 3; g = 0.10) interventions, but the difference was not statistically significant [13], highlighting the need for further evaluation of remotely delivered FCR interventions. More recently, an online self-managed but clinician-supervised web-based CBT program (iCanADAPT) demonstrated efficacy in reducing FCR relative to treatment as usual (i.e. access to family doctor and/or local mental health services) [26]. However, trials of two other self-guided digital FCR interventions, FoRtitude [27] and CAREST [28], found comparable FCR reductions in the intervention and control groups, possibly due to their primary use of traditional CBT techniques generally found to be less efficacious in reducing FCR [13], or limited intervention engagement.

Digital intervention engagement, defined as both the subjective experience of flow involving interest and attention, and the extent of usage of a digitally based intervention [29], is a key indicator of digital intervention feasibility and likely efficacy [30]. In-depth engagement measures are rarely reported for digital health interventions [31], despite Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials on eHealth (CONSORT-EHEALTH) recommendations [32]. Considering the variable non-usage and engagement levels reported [33, 34], it is critical to understand how participants engage with digital interventions and their various components and how engagement is related to psychological outcomes [35, 36].

To make FCR treatment more accessible, the efficacious face-to-face ConquerFear intervention [15] was adapted to a self-guided digital intervention (iConquerFear), and usability testing found that cancer survivors appreciated its flexibility and content design [22]. This study aimed to evaluate iConquerFear feasibility (uptake and engagement levels), and preliminary efficacy (changes in FCR 10 and 22 weeks after gaining access) with breast cancer survivors using the intervention as intended.

Methods

Trial design

This was a single-arm, non-blinded pilot trial approved by South-Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) Ethics Committee (reference number 2020/ETH0266).

Participants

Women were eligible to participate if they had (i) completed hospital-based adjuvant treatment for breast cancer with curative intent, (ii) no evidence of recurrence, (iii) sufficient English proficiency for informed consent and intervention engagement, (iv) internet and email access and (v) scored ≥ 13 on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory-Short Form (FCRI-SF) [37] indicating moderate-severe FCR (measure described below) [38]. Exclusion criteria included moderately severe or severe depression, and/or suicidal ideation.

Participants were recruited from February to June 2021 using four methods: (1) referrals from Cancer Council New South Wales, Queensland or Western Australia information and support telephone services, (2) social media advertisements, (3) clinician referrals from SWSLHD Cancer Centres and (4) emails to the Breast Cancer Network Australia (BCNA) Review & Survey Group, an online database of breast cancer research volunteers.

Sample size

Our target sample size was 60 women based on recommendations for pilot research [39,40,41]; hence, we aimed to recruit 75 women to allow for attrition.

Procedure

Prospective participants were emailed a link to an online participant information sheet, consent form and FCRI-SF [37] and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) screening questions [42] (further details in the outcomes section). A researcher contacted eligible participants to provide a study overview, answer questions and confirm participation. If consented, participants were given website access instructions and a unique login. The researcher called participants 1 week after recruitment to troubleshoot any technical issues experienced.

At their first login, participants were required to complete an online self-report baseline (T0) questionnaire. They were then recommended to sequentially complete iConquerFear modules over 10 weeks (i.e. one module per fortnight), although they had unrestricted access to all modules for 22 weeks. Participants were subsequently asked to complete post-intervention questionnaires 10 weeks (T1) and 22 weeks (T2) post-baseline.

Intervention

iConquerFear was derived from the face-to-face ConquerFear intervention, which targets unhelpful beliefs about worry (i.e. metacognitions) that play a central role in the development and maintenance of severe FCR according to the cognitive processing model of FCR [43, 44]. It uses contemporary CBT techniques from acceptance and commitment therapy and metacognitive therapy to reduce unhelpful metacognitions and intrusiveness of thoughts about recurrence [45]. Psychoeducation and therapeutic strategies are delivered via didactic and interactive written and audio-visual material organised into 6 modules, an optional welcome module and five therapeutic modules: (1) goal setting, (2) attention training, (3) detached mindfulness, (4) learning to live well and manage worry, and (5) treatment summary and relapse plans [22]. To facilitate engagement, the strategies of tunnelling (sequential progression through activities) [46], personalised feedback, tailored automated email reminders, interactive reflections and quizzes were integrated into iConquerFear [22]. A detailed description of the intervention is published elsewhere [22].

Measures

Self-reported demographic and clinical characteristics including age, gender, relationship status, cancer stage, time since diagnosis and treatment received were assessed at baseline.

Primary outcomes

Uptake

Acceptable uptake was pragmatically defined as ≥ 50% of the breast cancer survivors reporting moderate or higher FCR in screening agreeing to participate in iConquerFear. This would equate to a large number participants in a subsequent trial or implementation of iConquerFear in view of the prevalence of FCR and lack of broadly accessible treatments.

Engagement

The primary engagement measure was total time spent using iConquerFear, as used in previous studies [33, 34]. We suggested that participants spend about an hour working through each module and expected that they would need to spend at least 120 min using iConquerFear (i.e. the approximate time needed to complete 2 therapeutic modules) to reduce FCR. Participants were categorised as low (0–119 min usage), moderate (120–599 min usage) and high (600 + min usage) users. Engagement was deemed acceptable if > 50% of participants were moderate or high users.

Preliminary efficacy

This was measured by pre- to post-intervention changes in FCR severity assessed using the FCRI-SF, a widely used and validated subscale of the FCRI [37], across all three time points T0, T1 and T2 [3, 47]. The response scale for each item is on a 5-point Likert scale, between 0 (‘Not at all/Never’) and 4 (‘A great deal/Several times a day/hours/year’). Total scores range from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater FCR [37, 48].

Reliable change in FCR was calculated following Jacobson and Truax’s recommendations using the published Cronbach alpha (r = 0.88) of the English version of the FCRI [49] and the standard deviation of baseline FCRI-SF scores. Post-intervention FCRI-SF score below the clinical cutoff of 13 indicated clinically significant change [37].

Secondary outcomes

Secondary measures of engagement included number of logins, page views, and module/intervention completion. Dropout attrition (participants who withdrew from the study) and non-usage attrition (participants who did not complete any of Modules 1–5) were also measured [50]. Facilitators and barriers to iConquerFear engagement were captured through open-ended questions in the T1 survey and spontaneous participant feedback during follow-up.

Anxiety was measured using the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) [51], which assesses the presence of generalised anxiety symptoms in the past 2 weeks using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). Scores range from 0 to 21 and higher scores indicate worse anxiety.

Intrusive thoughts were measured using the 7-item intrusion subscale of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) [52, 53], which assesses distress caused by intrusive thoughts related to cancer in the past 7 days on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to extremely (4). Scores range 0–28 and higher scores indicate more intrusive thoughts.

Negative metacognitions were measured using the 6-item negative beliefs about the worry subscale of the Metacognitions Questionnaire (MCQ-30) [54], which assesses agreement with statements of beliefs about worry on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from do not agree (0) to agree very much (4). Subscale scores range 6–24 and higher scores indicate more maladaptive metacognition.

Depression was screened for using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [42], which assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms within the past 2 weeks using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to nearly every day (3). Scores range from 0 to 27, with scores ≥ 15 indicating moderately severe/severe depression. Scores ≥ 1 on item 9 ‘Thoughts you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way’ indicated suicidal ideation.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis was conducted via IBM SPSS Statistics version 27. An independent t-test was used to compare mean FCRI-SF scores between those eligible and ineligible for the study. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise study sample characteristics. Differences in baseline characteristics between user groups (low, moderate, high) were assessed using chi-squared tests, independent t-tests, one-way ANOVA, Wilcoxon rank-sum or Kruskal–Wallis tests, depending on variable type. Linear mixed models were used to assess changes in FCRI-SF, GAD-7, IES-R and MCQ-30 scores from T0 to T1 and T2. The mixed models included a random intercept to account for repeated measurements, and participant age and years since diagnosis as potential confounders. The association between FCR change and intervention user group (low, moderate, high) and intervention completion (yes/no) was assessed by inclusion of these variables, respectively, into the mixed model. All tests were two-sided, and a p value of < 0.05 was deemed significant.

Qualitative feedback from open-ended questions and spontaneous participant comments during follow-up was thematically analysed [55] to determine barriers and enablers to iConquerFear engagement and identify potential improvements. Feedback was analysed using a six-step process: SJ reviewed the data, generated preliminary codes and grouped codes into overarching themes. ABS and AB then worked with SJ to review, finalise and write-up themes.

Results

Participants

From February to July 2021, 107 breast cancer survivors were invited to participate. Active recruitment ceased once our target of 75 screened participants was reached, but 101 ultimately completed screening, 83 (83%) reported FCRI-SF scores ≥ 13, and 65 (64.4%) were eligible, with 26 excluded due to moderate/severe depression, and/or suicidal ideation (see Fig. 1). There was no significant difference between FCRI-SF scores of eligible (mean = 21.08, standard deviation (SD) = 4.2) and ineligible participants (mean = 20.88, SD = 7.2, p = 0.901).

CONSORT participant recruitment flow diagram. *Unable to track which participants completed the screening questionnaire, as the survey does not request identifiable data. aMultiple reasons may apply. bOne participant completed the screening questionnaire twice and was ineligible both times. cExcluding all withdrawn participants. Forty-seven participants had a 10-week access to iConquerFear

Feasibility (uptake)

Fifty-four (83.1%) of 65 eligible women agreed to participate in iConquerFear; thus, our feasibility target of enrolling at least 50% of eligible women was met. Six participants (11.3%) subsequently withdrew, three did not complete the baseline survey, and one was excluded as her data was lost when her account was reset to enable her to continue using the intervention after the study had ceased. Forty-four of 65 eligible participants (67.6%) completed the baseline survey and accessed the website. Thirty (63.8%) participants subsequently completed both the T1 (mean = 10.4, SD = 2.16 weeks post-T0) and T2 (mean = 25.3, SD = 1.5 weeks post-T0) questionnaire (see Fig. 1).

Sample characteristics

Eligible participants providing baseline data (n = 44) had a mean age of 55.3 years (SD = 9.8) and were a median of 4.0 years since diagnosis (IQR: 2.8.5). Most participants (70.4%) were married/partnered, had children (75.0%), had obtained a university degree (68.2%), were currently employed (68.2%), were born in Australia (68.2%) and primarily spoke English (86.4%). See Table 1 for other sample characteristics according to iConquerFear user group.

Feasibility (engagement)

Eight participants (17.0%) were classed as low users (0–119 min usage), 24 (51.1%) as moderate users (120–599 min usage) and 15 (31.9%) as high users (≥ 600 min usage). Thus, our target of greater than 50% moderate to high users was met. High users demonstrated greater engagement across all measures and were significantly more likely to complete the intervention (73%; p < 0.001).

Thirty-nine (83.0%) of 47 participants given 10-week intervention access completed at least the first therapeutic module; the other eight (17%) completed no modules. Thirty-three (70.2%) participants completed at least two out of five therapeutic modules; 17 (36.2%) participants completed Module 5 and the intervention as whole. The average percentage of iConquerFear completed was 64.5% (SD = 35.4). Median number of page views was 52.5 (IQR = 19–77), with a total of 464 logins (median = 8.0, IQR = 3–12), and a median login duration of 73 min.

Engagement correlates

User groups

As shown in Table 1, user group membership was significantly associated only with age (p = 0.043) and baseline FCR (p = 0.028). High users were older and had lower baseline FCR. Compared to moderate users:

-

1.

Older age was associated with being a high user (OR = 1.09, 95% CI 1.005–1.186, p = 0.038);

-

2.

Higher baseline FCR increased the likelihood of being a low user (OR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.004–1.585, p = 0.046).

Preliminary efficacy

Primary outcome

For the 27 participants with FCRI-SF data at all three time points, linear mixed models analysis showed FCR severity significantly decreased over time from T0 (mean = 19.93, SD = 3.9) to T1 (mean = 16.48, SD = 5.2, mean reduction (95%CI): − 3.44 (− 5.18, − 1.71), p = 0.0002, Cohen’s d = 0.74) and further decreased from T0 to T2 (mean = 15.41, SD = 4.8, mean reduction (95%CI): − 4.52 (− 6.25, − 2.78), p = < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.0) (Table 2). The significant reduction in FCR remained when the model was adjusted for age and years since diagnosis, respectively. Age and years since diagnosis were not associated with FCR (age beta: − 0.042 95%CI: (− 0.21, 0.13), p = 0.616; years since diagnosis beta: − 0.09 95%CI (− 0.44, 0.26), p = 0.598).

Reliable and clinically significant change in FCR

The reliable change criterion was calculated to be 3.68 (Cronbach alpha = 0.88 from literature, and baseline survey standard deviation = 3.82). Figure 2 shows the change in FCR from baseline (T0) to (A) post-intervention (T1) and (B) 3-month follow-up (T2), for the 27 participants with FCRI-SF data at all three time points. Seven (25.9%) participants experienced reliable and clinically significant improvement at T1 and six (22.2%) at T2.

Reliable and clinically significant change in fear of cancer recurrence (FCRI-SF scores). Figure description: change in fear of cancer recurrence between (A) pre- and post-treatment (T0 to T1) and (B) pre-treatment and 3-month follow-up (T0 to T2), for participants (n = 27) who completed the FCRI-SF at T0, T1 and T2. The diagonal line indicates no change. The horizontal and vertical lines indicate the FCRI-SF clinical cutoff of ≥ 13 pre- and post-treatment. Orange circle: no reliable or clinically significant change. Blue triangle: reliable, but not clinically significant change. Grey triangle: reliable and clinically significant change. Red circle: not reliable, but clinically significant change

Factors associated with level of FCR change

There was no difference in FCR change according to intervention user group (high vs moderate, p = 0.08), but those who completed the intervention had significantly lower FCR than those who did not (mean difference: − 3.8, 95%CI: − 6.5, − 1.1, p = 0.008).

Secondary outcomes

Compared to baseline (T0), there were significant decreases in intrusive thoughts at T1 (mean difference: − 0.32, 95%CI: − 0.54, − 0.11, p = 0.004) and T2 (mean difference: − 0.25, 95%CI: − 0.47, − 0.04, p = 0.02); negative metacognitions at T1 (mean difference: − 1.78, 95%CI: − 3.12, − 0.44, p = 0.01) and T2 (mean difference: − 1.89, 95%CI: − 3.23, − 0.55, p = 0.007); and anxiety at T2 (mean difference: − 1.63, 95%CI: − 3.22, − 0.04, p = 0.045), but not T1 (mean difference: − 1.0741, 95%CI: − 2.67, 0.52, p = 0.18). Significant reductions in secondary outcomes remained when the model was adjusted for age and years since diagnosis, respectively. See Table 2 for further details.

Qualitative evaluation of iConquerFear

Thirty-two of 47 participants gave qualitative feedback via open-ended questions and spontaneous comments during follow-up. Three key themes were generated from thematic analysis: acceptability of iConquerFear, challenges with engagement and recommendations for improvement. Participants largely perceived iConquerFear to be an informative, reassuring, useful and effective tool for managing FCR. However, engagement was sometimes limited by technical and time barriers, and some wanted greater signposting of resources and demographic diversity of cancer survivors featured to make content easier to navigate and relate to. See Table 3 for description of each theme and illustrative quotes.

Discussion

There is a critical need for scalable FCR interventions to address cancer survivors’ great unmet need for managing FCR. This pilot study evaluated the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear, a self-guided digital intervention, to reduce FCR. Feasibility was demonstrated by > 80% of eligible participants enrolling in iConquerFear and > 80% recording moderate to high use. Older participants were more likely to engage with iConquerFear, while those with higher baseline FCR were less likely. On average, participants reported significant reductions in FCR from baseline to post-intervention of a medium to large effect size, with improvements maintained 3 months post-intervention; about one-quarter reported clinically significant improvements at both post-intervention time points. Change in FCR was not significantly associated with intervention engagement, perhaps due to limited statistical power. Suggested changes to increase iConquerFear engagement and efficacy included easier navigation and greater demographic diversity of featured cancer survivors.

The potential of online FCR self-management interventions is unlikely to be realised unless they successfully engage cancer survivors. iConquerFear engagement was greater than similar interventions like CAREST, where limited usage was suggested to explain its lack of efficacy [28], and comparable to FoRtitude, which also averaged 8 logins and about 60% of participants completing two-thirds of the intervention [27]. The relatively high iConquerFear engagement levels may be due to its theory- and person-based development, which facilitated flexible access, easy navigation and content satisfaction/engagement using techniques such as content tunnelling, interactive exercises and tailored feedback [22].

While initial iConquerFear engagement was relatively high, as with other digital interventions (e.g. FoRtitude [27]), it declined, with only 36% of participants completing all modules, compared with 67% of face-to-face ConquerFear participants who completed all five sessions [15]. We predicted that participants would need to spend at least 2 h using iConquerFear (i.e. the estimated time to complete 2 modules) to derive benefit, based on the ConquerFear RCT and iConquerFear usability study feedback, but there is limited evidence to suggest what ‘dose’ of digital self-guided interventions is needed to have an effect [56]. Some iConquerFear participants may have benefitted from early intervention components, such as the values clarification card sort task in Module 1, and chosen to focus on applying that learning, rather than continue with iConquerFear. The FoRtitude RCT found higher intervention use was related to greater FCR reduction [27]. Our study did not find this association, perhaps because it was not powered to detect it, or it may reflect the variable benefit participants gained from different intervention components and amounts.

Correlates of engagement

Older age was associated with greater iConquerFear engagement, which was unexpected as younger age is associated with greater acceptability of online self-management amongst cancer survivors [57]. However, age has demonstrated equivocal associations with engagement in online psychological interventions generally [58]. Many studies reporting correlations between older age and lower engagement were conducted several years ago. These studies may not reflect increasing digital literacy in older people in the past decade, with older cancer survivors more often seeking health guidance on the Internet [59], enabling them to better engage with digital interventions. Online recruitment (e.g. via email listserv) of some participants and the generally high education levels of our sample may also have produced a more digitally literate sample of cancer survivors, with older women having greater opportunities to engage with iConquerFear. Qualitative feedback indicated that COVID-19 negatively affected engagement by younger women, who reported greater home pressures and limited time consistent with the greater burden of caregiving and home duties during lockdowns on younger women generally [60].

Higher baseline FCR was also associated with lower iConquerFear engagement. This is consistent with a study of uptake and adherence to online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (eMBCT), which found non-users had higher baseline FCR than users [33]. In general, mixed associations between baseline symptom severity and engagement with online psychological interventions have been found [58]. Higher FCR has been associated with greater avoidance coping [61], which may lead to poor intervention engagement. Participants with higher FCR may also have perceived iConquerFear as insufficiently intensive to address their fears, limiting engagement. Qualitative feedback indicated some with higher FCR found the self-guided aspect of iConquerFear challenging, as they had to confront their FCR with limited perceived support. Clearer explanation of what iConquerFear involves, how to best use the intervention and more prominent links to in-person support may help increase uptake and engagement. Self-guided interventions may be best suited to people with moderate FCR, with more intensive approaches better suited to those with severe FCR [62]. Stepped/matched care FCR treatment models, where patients are allocated to interventions they are most likely to engage with and benefit from based on FCR severity, have demonstrated promise in FCR management [63].

Another option to augment engagement with interventions like iConquerFear and increase their suitability for those with more severe FCR, without overly limiting their scalability, could be to add therapist guidance. In a pilot RCT of iCanADAPT, an online self-guided, but therapist-supervised CBT program, participants averaged 64.3 min (SD = 40 min) of therapist contact; 40/52 (77%) completed all eight treatment lessons and experienced significantly greater reductions in total FCR than treatment as usual controls immediately post-intervention and at 3 months follow-up [26]. Telecoaching (i.e. 4 weekly telephone-based motivational interviews) promoted greater engagement with FoRtitude, which was associated with larger FCR reductions [27]. Relatively minimal contact with a coach or therapist may improve engagement (and efficacy in turn) and a RCT of therapist-guided iConquerFear is underway in Denmark [64].

Preliminary efficacy

iConquerFear demonstrated preliminary efficacy, with medium-large-sized FCR reductions at post-intervention (d = 0.74) and 3 months follow-up (d = 1.0), similar to within-group reductions for face-to-face ConquerFear participants (d = 0.77) [15]. As in the ConquerFear RCT, there were also significant reductions in anxiety, which, like FCR improvements, were maintained at 3-month follow-up. Comparison with other online FCR intervention trials is complicated by the different measures, methods and analyses used. The preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear may be due to its contemporary CBT approach, shown to be more effective than traditional CBT techniques [13], such as those largely used in CAREST [28] and FoRtitude [27]. Reductions in FCR were accompanied by decreases in maladaptive metacognitions and distress related to intrusive thoughts about cancer, previously shown to partially mediate the effects of ConquerFear on FCR [45]. Our pilot study was not powered to test mediation models and with no control group decreased maladaptive metacognitions and intrusive thoughts cannot be causally attributed to the intervention. However, concurrent reductions in FCR, unhelpful metacognition and intrusive thoughts suggest a possible mechanism for the observed improvements in FCR consistent with the cognitive processing model of FCR [43].

Despite promising FCR reductions on average, only a quarter of participants reported clinically significant improvement. This could partly be due to the criteria for clinically significant change used, which meant that some participants reporting severe FCR initially experienced sizeable reductions in FCR without going below the clinical cutoff of 13. Establishing a minimally important difference on the FCRI-SF would mitigate this problem. Issues with longer term survivors (approximately 5 years post-diagnosis in our sample) being more likely to score highly on certain FCRI-SF items (e.g. ‘How long have you been thinking about the possibility of cancer recurrence?’) may also increase the difficulty of reducing scores below the clinical cutoff [3]. FCR scores may also have been inflated for many participants recruited shortly before a major COVID outbreak in Australia, as concerns about the impact of COVID on cancer management have been associated with FCR [65].

Potential improvements

iConquerFear was generally seen as an engaging and useful tool for self-managing FCR, as per previous usability testing, but improvements were suggested. Participants’ main critique was that some content was ‘impersonal’ or ‘unrelatable’, a common challenge for self-guided interventions. We tried to personalise iConquerFear by giving participants feedback tailored according to information provided while using iConquerFear, but much of the intervention content was fixed and due to budget constraints, a single breast cancer survivor featured in videos. In future modifications, the content, including the demographics and experiences of cancer survivors featured, should ideally be tailored according to user characteristics, as tailoring improves engagement [66].

Strengths and limitations

iConquerFear was adapted from the efficacious face-to-face ConquerFear intervention using a person-based approach, maximising the likelihood of feasibility and preliminary efficacy being shown in this pilot study. We screened and evaluated participants’ FCR using a well-validated measure and used comprehensive measures of iConquerFear engagement. A key study limitation was the lack of a control group, meaning that observed reductions in FCR cannot be attributed to iConquerFear specifically and may be due to expectation effects or spontaneous recovery. The relatively small sample also limited statistical power to identify factors associated with the preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear, such as intervention usage, and control for potential confounders. Future research could use a Multiphase Optimisation Strategy (MOST) framework, as per the FoRtitude trial [27], to efficiently evaluate the efficacy of both the intervention overall and individual intervention components. This may aid development of a shorter version of iConquerFear including only the most effective components, which may augment intervention engagement and benefit.

iConquerFear was evaluated in a well-educated sample of survivors of localised breast cancer who were largely Australian-born and spoke English as their first language, so our study results may not generalise to other cancer survivors. While our finding that older age was associated with greater iConquerFear engagement challenges the notion that digital health interventions may not be suitable for older cancer survivors, the use of online recruitment may have resulted in a more digitally literate sample of cancer survivors, despite recruiting participants from multiple sources to try and increase diversity. There is a critical need to evaluate digital health interventions in a range of participants, including from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, with rare and advanced cancers, and varied degrees of digital literacy to ensure that they deliver on their promise to increase the accessibility and equity of cancer survivorship care when they are implemented in routine care.

Conclusion

iConquerFear is a feasible self-guided digital intervention for reducing FCR, as evidenced by high engagement levels. Engagement could be further improved through easier navigation and increased tailoring of content to match user characteristics. Preliminary efficacy in reducing FCR out to 3 months needs RCT confirmation, ideally with participants from diverse backgrounds. iConquerFear may be most suitable for people with moderate FCR. Future integration into FCR stepped care models including more intensive options should be considered.

Data availability

Data available within the data or its supplementary materials.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0272-z.

Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, et al. From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3265–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3272-5.

Smith AB, Costa D, Galica J, et al. Spotlight on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI). Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:1257–68. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S231577.

Luigjes-Huizer YL, Tauber NM, Humphris G, et al., What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2022;n/a(n/a); https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5921

Williams JTW, Pearce A, Smith AB. A systematic review of fear of cancer recurrence related healthcare use and intervention cost-effectiveness. Psychooncology. 2021;30(8):1185–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5673.

Bergerot CD, Battle D, Philip EJ, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. JCO Oncology Practice. 2020;16(11):e1264–71. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00105.

Nahm SH, Blinman P, Butler S, et al. Factors associated with fear of cancer recurrence in breast and colorectal cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study of cancer survivors. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2021;17(3):222–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13434.

Crist JV, Grunfeld EA. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):978–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3114.

Cunningham SJ, Patton M, Schulte F, et al. Worry about somatic symptoms as a sign of cancer recurrence: prevalence and associations with fear of recurrence and quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2021;30(7):1077–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5647.

Magnani C, Smith AB, Rey D, et al., Fear of cancer recurrence in young women 5 years after diagnosis with a good-prognosis cancer: the VICAN-5 national survey. J Cancer Survivorship. 2022;https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01193-0.

Vandraas KF, Reinertsen KV, Kiserud CE, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence among young adult cancer survivors-exploring long-term contributing factors in a large, population-based cohort. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(4):497–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00943-2.

Hall DL, Luberto CM, Philpotts LL, et al. Mind-body interventions for fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2546–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4757.

Tauber NM, O’Toole MS, Dinkel A, et al. Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2899–915. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.00572.

Butow PN, Bell ML, Smith AB, et al. Conquer fear: protocol of a randomised controlled trial of a psychological intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):201. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-201.

Butow PN, Turner J, Gilchrist J, et al. Randomized trial of ConquerFear: a novel, theoretically based psychosocial intervention for fear of cancer recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4066–77. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.73.1257.

Clover KA, Mitchell AJ, Britton B, et al. Why do oncology outpatients who report emotional distress decline help? Psychooncology. 2015;24(7):812–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3729.

Skrabal Ross X, Gunn KM, Olver I, et al., Online psychosocial interventions for posttreatment cancer survivors: an international evidence review and update. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2020;14(1).

Bokolo Anthony J. Use of telemedicine and virtual care for remote treatment in response to COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Syst. 2020;44(7):132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01596-5.

Shaw J, Kamphuis H, Sharpe L, et al., Setting an international research agenda for fear of cancer recurrence: an online Delphi consensus study. Front Psychol. 2021;12; https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.596682.

Lehmann J, Buhl P, Giesinger JM, et al. Using the Computer-based Health Evaluation System (CHES) to support self-management of symptoms and functional health: evaluation of hematological patient use of a web-based patient portal. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(6):e26022. https://doi.org/10.2196/26022.

Smith AB, Rincones O, Heiniger L, et al., Online psychological self-management intervention for testicular cancer survivors (e-TC 2.0): promising acceptability and preliminary efficacy, but limited feasibility. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract. 2020;2(3)

Smith AB, Bamgboje-Ayodele A, Butow P, et al. Development and usability evaluation of an online self-management intervention for fear of cancer recurrence (iConquerFear). Psychooncology. 2020;29(1):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5218.

Aaronson NK, Mattioli V, Minton O, et al. Beyond treatment - psychosocial and behavioural issues in cancer survivorship research and practice. Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2014;12(1):54–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcsup.2014.03.005.

EscrivaBoulley G, Leroy T, Bernetière C, et al. Digital health interventions to help living with cancer: a systematic review of participants’ engagement and psychosocial effects. Psychooncology. 2018;27(12):2677–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4867.

Carlbring P, Andersson G, Cuijpers P, et al. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;47(1):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115.

Murphy MJ, Newby JM, Butow P, et al. Randomised controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for clinical depression and/or anxiety in cancer survivors (iCanADAPT Early). Psychooncology. 2020;29(1):76–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5267.

Wagner LI, Tooze JA, Hall DL, et al. Targeted eHealth intervention to reduce breast cancer survivors’ fear of recurrence: results from the FoRtitude randomized trial. JNCI: J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1495–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab100.

van Helmondt SJ, van der Lee ML, van Woezik RAM, et al. No effect of CBT-based online self-help training to reduce fear of cancer recurrence: first results of the CAREST multicenter randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2020;29(1):86–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5233.

McLaughlin M, Delaney T, Hall A, et al. Associations between digital health intervention engagement, physical activity, and sedentary behavior: systematic review and, eta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e23180. https://doi.org/10.2196/23180.

Perski O, Blandford A, West R, et al. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(2):254–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1.

Koneska E, Appelbe D, Williamson PR, et al. Usage metrics of web-based interventions evaluated in randomized controlled trials: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(4): e15474. https://doi.org/10.2196/15474.

Eysenbach G. CONSORT-EHEALTH: Improving and standardizing evaluation reports of web-based and mobile health interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e126. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1923.

Cillessen L, van de Ven MOM, Compen FR, et al. Predictors and effects of usage of an online mindfulness intervention for distressed cancer patients: usability study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e17526. https://doi.org/10.2196/17526.

van den Berg SW, Peters EJ, Kraaijeveld JF, et al. Usage of a generic web-based self-management intervention for breast cancer survivors: substudy analysis of the BREATH trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e170. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2566.

Børøsund E, Cvancarova M, Ekstedt M, et al. How user characteristics affect use patterns in web-based illness management support for patients with breast and prostate cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2285.

Donkin L, Christensen H, Naismith SL, et al. A systematic review of the impact of adherence on the effectiveness of e-therapies. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e52. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1772.

Simard S, Savard J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):481–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0424-4.

Fardell JE, Jones G, Smith AB, et al. Exploring the screening capacity of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory-Short Form for clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2018;27(2):492–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4516.

Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(2):307–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2002.384.doc.x.

Sim J, Lewis M. The size of a pilot study for a clinical trial should be calculated in relation to considerations of precision and efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(3):301–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.011.

Viechtbauer W, Smits L, Kotz D, et al. A simple formula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(11):1375–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.014.

Thombs BD, Benedetti A, Kloda LA, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8), and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for detecting major depression: protocol for a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analyses. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):124. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-124

Fardell JE, Thewes B, Turner J, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):663–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0512-5.

Smith AB, Sharpe L, Thewes B, et al. Medical, demographic and psychological correlates of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) morbidity in breast, colorectal and melanoma cancer survivors with probable clinically significant FCR seeking psychological treatment through the ConquerFear study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(12):4207–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4294-y.

Sharpe L, Turner J, Fardell JE, et al. Psychological intervention (ConquerFear) for treating fear of cancer recurrence: mediators and moderators of treatment efficacy. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(5):695–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00788-4.

Pugatch J, Grenen E, Surla S, et al. Information architecture of web-based interventions to improve health outcomes: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e97. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7867.

Thewes B, Butow P, Zachariae R, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic literature review of self-report measures. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):571–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2070.

Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2008;17(3):241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0444-y.

Lebel S, Simard S, Harris C, et al. Empirical validation of the English version of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):311–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1088-2.

Neve MJ, Collins CE, Morgan PJ. Dropout, nonusage attrition, and pretreatment predictors of nonusage attrition in a commercial web-based weight loss program. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):e69. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1640.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41(3):209–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004.

Weiss DS, The Impact of Event Scale: revised, in Cross-cultural assessment of psychological trauma and PTSD, JP Wilson and CS-k Tang, Editors. 2007; Springer US: Boston, MA. 219–238.

Wells A, Cartwright-Hatton S. A short form of the metacognitions questionnaire: properties of the MCQ-30. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(4):385–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00147-5.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Short CE, DeSmet A, Woods C, et al. Measuring engagement in eHealth and mHealth behavior change interventions: viewpoint of methodologies. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):e292. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9397.

Jansen F, van Uden-Kraan CF, van Zwieten V, et al. Cancer survivors’ perceived need for supportive care and their attitude towards self-management and eHealth. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(6):1679–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2514-7.

Beatty L, Binnion C. A systematic review of predictors of, and reasons for, adherence to online psychological interventions. Int J Behav Med. 2016;23(6):776–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9556-9.

Haase KR, Sattar S, Holtslander L, et al. The role of Internet cancer information for older adults with cancer: perspectives of older adults and healthcare professionals. Int J Older People Nurs. 2020;15(2):e12303. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12303.

Alon T, Doepke M, Olmstead-Rumsey J, et al., The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. 2020; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Maheu C, Singh M, Tock WL, et al., Fear of cancer recurrence, health anxiety, worry, and uncertainty: a scoping review about their conceptualization and measurement within breast cancer survivorship research. Front Psychol. 2021;12; https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644932.

Pradhan P, Sharpe L, Menzies RE. Towards a stepped care model for managing fear of cancer recurrence or progression in cancer survivors. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:8953–65. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S294114.

Lynch FA, Katona L, Jefford M, et al., Feasibility and acceptability of Fear-Less: a stepped-care program to manage fear of cancer recurrence in people with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9); https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092969.

Lyhne JD, Smith AB, Frostholm L, et al. Study protocol: a randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of therapist guided internet-delivered cognitive therapy (TG-iConquerFear) with augmented treatment as usual in reducing fear of cancer recurrence in Danish colorectal cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06731-6.

Zomerdijk N, Jongenelis M, Short CE, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress, unmet supportive care needs, and fear of cancer recurrence among haematological cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(12):7755–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06369-5.

Short C, Smit ES, and Crutzen R, Measuring psychological constructs in computer-tailored interventions: novel possibilities to reduce participant burden and increase engagement. 2021; PsyArXiv.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Cancer Councils, Breast Cancer Network Australia and SWSLHD for help with recruitment and to all the people living with and beyond cancer who participated. iConquerFear was developed with invaluable consumer input from Marj Salter, George Fishman, Jan Antony, Alison Button‐Sloan, Derek Cunningham, Max Shub and Chris Goodman. iConquerFear is based on ConquerFear, originally developed by a team of investigators under the auspices of the Psycho‐oncology Co‐operative Research Group (PoCoG), and with continued PoCoG input.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This trial was funded by an Ingham Institute Breast Cancer Research Grant, made possible by charitable donations through Narellan Rotary Club.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS, AB, PB, BK and MS conceptualised and designed the study. BS, AB, PB, BK, MS, JT, LS, JF, LB, AP, BT, JB, DC and AG contributed to the development of iConquerFear. Study protocols and materials were prepared by BS, AB and VW and reviewed by PB, BK and MS. KL, LM, BH, AB and RH aided recruitment. AB, OR and SJ did participant data collection and follow-up. FG, BS and SJ did the analysis. BS, AB and SJ drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and edited subsequent versions and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the South-Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 2020/ETH0266).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that participants provided informed consent for publication of anonymised and aggregated data.

Conflict of interest

iConquerFear was developed using the My Digital Health platform, which was created by Professor Britt Klein and an external consultancy IT group (Retsim Pty Ltd), and is published by Federation University Australia, Ballarat, Australia.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Smith and Bamgboje-Ayodele are joint first authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, A.‘., Bamgboje‐Ayodele, A., Jegathees, S. et al. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of iConquerFear: a self-guided digital intervention for fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv 18, 425–438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01233-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01233-9